Search This Blog

15.10.23

CHANGING THE RHETORIC OF MOUNTAIN BIKING

DOES RELIGION DRIVE MEN MAD?

THE IMPLACABLE NATURE OF THE IDEA

I observe, as many do, the unfolding disaster in Gaza and thoughts emerge unbidden in my mind.

I wonder about countries and religion and how so often these modes of supposed salvation drive men and women into vortices of complete madness leading to unthinkable cruelty and barbarism.

How human men (and they are mostly men) will murder children, rape women and torture their fellow humans with gleeful commitment, even enthusiasm for inflicting the maximum level of pain and humiliation.

How is all this possible?

My answer is expressed with all humility as these are simply my thoughts, those motes of dust in the wind. But I strive for some anchor for the immense pain I feel in my heart upon watching this unfolding cataclysm of hatred and horror in the Middle East.

My sense is that this all begins in the mind. That what we witness here is a result of thoughts and imagination replacing reality.

Let us take a comparison. Look at what we call countries. Do they exist? Well yes, we consider we come from a particular country. When we are asked the question where are you from we will often reply, well I'm from the UK or I am from South Africa or I am from Brazil or I am an Israeli or I am a Palestinian.

In this sense our country of birth or a new nationality we have taken on becomes a large part of what we may refer to as our identity, it describes part of what we perceive as our essential Self, our being.

Then we may be asked by this imaginary interviewer-What are you about? What do you believe? And often, what do you do?

But let’s pause a moment at the question of our country. What is a country? Is it not simply an idea?

There are no real lines of demarcation in nature that determines what group of Homo sapiens will live in a specific area. Those borders are created inside someone’s head and often collide with other ideas of conquest, war, colonisation and economic expansion.

These ideas collect behind the original idea of ‘country’ and what is an imaginary reality becomes more real than the actual reality. An endless train of countless carriages hurtling on its way to another constructed idealised reality.

Because the fact is that countries do not exist in actual reality. In many ways they are fictionalised entities that are concretised in imaginary nature but they cannot exist in nature because they are not real. They are ideas.

If we imagine the human species were to instantly vanish what would be left? Well there would be buildings, temples, prisons, immense cities, ports, lots of walls and fences, military bases and seaside resorts. But there would be no countries. Because countries do not exist in independent reality. They are ideas of place rather than place itself.

If we look at a mountain, say Kilimanjaro, we can see that it exists in nature. It is an existential fact that is not dependent on thoughts or belief systems for its being a concrete part of nature. Unlike countries, which only truly exist in the minds of their inhabitants and therefore have no concrete existence in nature.

Is it not the saddest thing that what drives the great wars and slaughters is simply an idea?

Perhaps we should get rid of this idea and simply live on our planet?

Religion too is perhaps the most powerful of these ideas based as it is on the single strongest driver of division between humans - the idea of God. And then inevitable meditations upon the nature of this God.

Whether it be called Jesus or Jehovah or Allah or the Lord Buddha or the Creator, or Shiva, these are all versions of the same idea. An imaginary Being that requires a set of rules and beliefs and behaviour to be placated or worshipped or honoured. Rules that can be infringed with resulting punishments. Highly varied schema of intolerance is directed between these different ideas and it underpins the continuing holocaust between humans located in their various idealised territories that we call countries.

I will nail my own colours to the mast. I do not know if there is a God. I choose not to believe that there is because I choose not to believe in something I cannot understand. If God has existence it would surpass our understanding containing within itself all meaning.

In the seventeenth century Spinoza made the case that God must be part of natural law and that therefore miracles cannot have taken place because they are in defiance of natural law and that consequently the Bible must be taken as metaphor, not fact. He also stated that this God acting in accord with natural law, with Nature, is highly unlikely to require strictly determined rules of behaviour or ceremonial activity or specific dress as these are simply ideas from the imagination of humans.

Spinoza’s ethics, massively simplified, state that humans should live in accordance with natural law and thus acquire what he called ‘blessedness’.

I can live with this ‘idea’, it makes sense to me to seek ‘blessedness’ though I struggle with the acquisition.

However given my own ‘ideas’ on the subject I am most content to allow my fellow humans to worship and pray to whatever God they imagine and I wish them comfort from it. I do not however consider this gives them any right to predate and destroy and discriminate on those who interpret this most ungraspable of notions in a different way from themselves.

I was brought up in the Roman Catholic Faith and even attended a Seminary as a boy, destined for the Priesthood, when, as a devastated 14 year old I came to the realisation that this was all nonsense upon stilts.

Perhaps then we should get rid of both ideas. That of Nations and that of Religions. Perhaps we should just be in the world.

None of this helps the men, women and children of Gaza facing annihilation or the avenging Israeli’s who have lost their loved one’s in Hamas’s shocking assault.

But like many others I stand mute in the face of this unfolding catastrophe. I stand mute, looking at the cold, hard and vengeful eyes of the leaders and the blood of the innocent which will once again flow into the river of human time and the circle of hate growing, ever growing. Once again I stand mute and uncomprehending at the implacable nature of The Idea.

18.6.23

26.3.23

ME AND BOB DYLAN

23.10.22

I saw this recently on the 'Recommendo' newsletter. It looks like a good set of questions. Twitter thread of self-fulfillment questions |

Greg Isenberg says he asked 1 billionaire, 1 PHD math professor and 1 99-year-old man what self-reflection questions they asked themselves and then he shared them in a Twitter thread, as a list of questions to make you feel more fulfilled in life, love & career. The ones I’m pondering are:

|

1.10.22

The Irresistible Rise of Helen DeWitt-Currently this Blog's favourite author!

'Lightning Rods'. Published 2011. Started 16.8.22-Finished 31.8.22

Thoughts? Beautifully written. Remarkably funny. Huge degree of intelligence on the part of the writer. Could not recommend this enough! Sadly this couldn't have been written by a man these days.

The mechanism for preventing sexual harassment suits against male workers in corporations is given full expression. My favourite novel of 2022 until, that is, I started reading 'The Last Samurai' - More to follow on that.

A Polemic on the current practice of Social Work with Children and Families

The primary object of social work is to create a society where it has no need to exist.

Right away we are approaching a battle. A battle against systems that would deliberately create a dedicated organisation where a specific type of activity which we may call surveillance social work is brought to bear upon the poor. Surveillance /measurement/ Secret monitoring/ Professional Cabals/

A mean spirited social work that fully participates in the poverty and inequality and discrimination against those who may be poor while paying for families to live in overcrowded and filthy accommodation, children to be abandoned to private social work provisions lacking any sense of obligation and service to anything other than profit. (WELL CLEARLY I’M GOING TO GET LOTS OF MY CHEST!)

The primary object of current social work however, appears to be to engage in a project of technical bureaucratic intervention in a society that invades every aspect of the lives of the poor, most particularly by a creeping intervention in family life, without reference to the capacity for transformation and, even if such transformation were positively acknowledged, without the resources or skills to accomplish it in any meaningful sense.

In this project that I shall call neo-liberal welfarism, the social workers are joined in their interventions by the various tribes of the welfarist universe, united by this project of child protection under the disguise of soft policing by chronic programmes of endless assessment, innumerable meetings, diagnostic determinations, psychological categorisations and psychiatric considerations, various cabals of professionals-only discourse, and endless judgement and measurement. Labels of all kind abound with all manner of evidential weight attached. All underpinned by a legal system chronically obsessed with process and timescales over potential and possibilities and legislation often enacted in fear of further tragedy rather than in hope of better outcomes, with all the practice implications that are embodied in fear of failure, and public excoriation in the hallowed and considered prose of the gutter journalists who delight in the character assassination and moral dismemberment of all social workers unfortunate enough to be involved in the tragedy of the death of a child at the hands of his or her parents.

And so we proceed, marking our milestones by the death of the innocents and 'drawing conclusions on the wall.' We must be risk averse, ever watchful, we must record every detail, we must act before disaster strikes. We must establish modes of ruthless surveillance. And as the gutter press so gleefully command, we must stop these evil monsters bent on murdering children, in their tracks. We must be relentless and give them the damnation they so richly deserve.

5.3.22

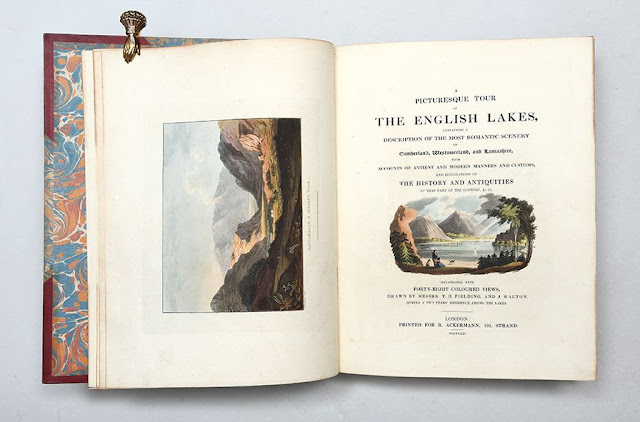

WALTER REDFERN ON PUNS/PICTURESQUE TOUR OF THE ENGLISH LAKES/THE RUSSIAN INVASION OF UKRAINE

RESISTANCE. BY SIMON ARMITAGE

It’s war again: a family

carries its family out of a pranged house

under a burning thatch.

The next scene smacks

of archive newsreel: platforms and trains

(never again, never again),

toddlers passed

over heads and shoulders, lifetimes stowed

in luggage racks.

It’s war again: unmistakable smoke

on the near horizon mistaken

for thick fog. Fingers crossed.

An old blue tractor

tows an armoured tank

into no-man’s land.

It’s the ceasefire hour: godspeed the columns

of winter coats and fur-lined hoods,

the high-wire walk

over buckled bridges

managing cases and bags,

balancing west and east - godspeed.

It’s war again: the woman in black

gives sunflower seeds to the soldier, insists

his marrow will nourish

the national flower. In dreams

let bullets be birds, let cluster bombs

burst into flocks.

False news is news

with the pity

edited out. It’s war again:

an air-raid siren can’t fully mute

the cathedral bells -

let’s call that hope.

Simon Armitage

Simon Armitage's (Our Poet Laureate in the UK) Poem is hearfelt and so moving. The prospect of a war at the near end of the first quarter of the 21st Century is almost unbelievable. My own view is that it matters little to bullies that you stand looking on their crimes wringing your hands and decrying the outrage of it. Bullies, psychopaths and murderers only understand a response as forceful as theirs or greater. Then they often seem to disappear as if they only existed as a result of our fear of them, which may, in fact be the case.

The open-hearted response of the British to the assistance of Ukrainian refugees is to be honoured. However I am puzzled about the country's warm response to the Ukrainians compared to the hostile environment and unwelcome meted out to Syrians, Latino's and Africans. Could it possibly be that the Ukrainians are white "like us" and not brown, black and yellow people and therefore "not us but other?"

That would of course mean that the broken bodies of Africans and middle eastern peoples are worth less, that their lives have less meaning. How could it be possible that such poisonous racism could have taken root in the hearts of the Brits?

Of course our black, brown and yellow brothers and sisters have known that for some time.

So we must remember these Iliads are woven in the crook'd dreams of the hollow men and will always be, until our consciousness develops to the elementary point that such monstrosities become unthinkable, even unimaginable. As a species we are not there yet! Not by a long way!

May your God go with you and may all our Gods preserve and support the brave Ukrainians in their hour of War. Love and Will. In balance.

17.1.22

A library the internet can’t get enough of!

Every year or so, the library in the photograph above — with stacks of books piled high and buttery lamplight aglow — resurfaces on the internet. It is often (erroneously) attributed to the author Umberto Eco, or said to be in Italy or Prague. |

In fact, Kate Dwyer reports for The Times, the library is not in Europe. It doesn’t even exist anymore. But when it did, it was the home library of the Johns Hopkins professor Dr. Richard Macksey — a book collector, polyglot and scholar of comparative literature. His book collection clocked in at 51,000 titles, some 35,000 of which eventually made their way into the university’s libraries. |

Why do people love this image so much? Don Winslow, the author and political activist, who recently posted a photograph of the library on Twitter, said it was “as stunning as a sunset.” Ingrid Fetell Lee, the author of the blog the Aesthetics of Joy, pointed at the photo’s sense of plenitude: “There’s something about the sensorial abundance of seeing lots of something that gives us a little thrill,” she said. |

And what would Dr. Macksey think, if he knew his library had taken on a life of its own? “My dad liked nothing better than sharing his love of books and literature with others,” his son, Alan Macksey, said. “He’d be delighted that his library lives on through this photo.” |

16.1.22

I'm back!

Ok Happy and Healthy 2022. May your dreams fall like feathers of glory around you as they come to beautiful fruition!

I've been away. Spiritually, intellectually emotionally. UNPRESENT. I'll write about it over the coming months.

For now I have just seen the comments that have been made and been awaiting moderation for over a year for which I am truly sorry. I will answer every one over the next few weeks.

I will try to post weekly from here in -and from the bottom of my heart thank you for reading my little blog!

9.1.22

From my Poem 'The Twenty One insights'.

Now he cast his nets at my request,

and all he said reeked of naked truth.

‘First, wake up! And sniff the guiding wind,

the teaching that is written in the sky,

written in the clouds for all to see.

Men were stretched to look up at the stars,

not to snuffle in the clotted mud,

or labour for some crook in factories

Like icebergs calving in a frozen sea,

his words touched me like sea-dreams deep within.

Touched that yearning that I know is in me.

‘You cannot walk through life with eyes tight shut!

And neither is this role a waking dream.

Sleep or wake-each must have it’s place,

and don’t forget to actually breathe!

To breathe is to inhale the dust of stars.

18.9.21

IN THE MIDDLE OF THE ACTUAL CREATIVE MOMENT-TIM ROUGHGARDEN

Sometimes we walk in the moments history is born and made. As Tim Roughgarden states below introducing his new lecture series-now is such a moment. This is from Tyler Cowen's Blog, Marginal Revolution.

It’s worth recognizing that we’re currently in a particular moment in time, witnessing a new area of computer science blossom before our eyes in real time. It draws on well-established parts of computer science (e.g., cryptography and distributed systems) and other fields (e.g., game theory and finance), but is developing into a fundamental and interdisciplinary area of science and engineering its own right. Future generations of computer scientists will be jealous of your opportunity to get in on the ground floor of this new area–analogous to getting into the Internet and the Web in the early 1990s. I cannot overstate the opportunities available to someone who masters the material covered in this course–current demand is much, much bigger than supply.

And perhaps this course will also serve as a partial corrective to the misguided coverage and discussion of blockchains in a typical mainstream media article or water cooler conversation, which seems bizarrely stuck in 2013 (focused almost entirely on Bitcoin, its environmental impact, the use case of payments, Silk Road, etc.). An enormous number of people, including a majority of computer science researchers and academics, have yet to grok the modern vision of blockchains: a new computing paradigm that will enable the next incarnation of the Internet and the Web, along with an entirely new generation of applications.

9.7.21

Response to a piece in the Sunday Times by Matthew Syed

Matthew Syed seems one of the more insightful journalists working for the Murdochs though I continue to have obvious problems with Journalists musing on the erosion of ‘liberal democracy’ (whatever that is) whilst taking the filthy lucre of one who is a prime eroder of said democracy.

Here we have a continuation of a genre of journalism, realpolitik, personal anecdote, frankly expressed insight, tell it all-warts and all, which seems to be exploding. It’s breast beating but disguised as insight. It bemoans the loss of what, in reality, never existed, because specific interests with paws on the levers of power cannot in what might be laughingly referred to as ‘their view’ allow IT to happen. What that IT is, is a functional, widespread, engaging and engaged, honest and transparent political system that responds to a series of checks and balances that are beyond the control of individuals or interest groups and to which all subscribe on pain of political disgrace and annihilation.

What we have instead is a philosophical hotch-potch of self interested think tanks, lobbyists, millionaires and billionaires, Corporate interests, Big Pharma, the Military Industrial Complex, Control of media, a militarised Police Force, State Erosion and Public Services nullified with their replacement by inefficient and unqualified private providers seeking profit from said Services.

The family silver has, of course, been sold. The grounds also hived off for luxury flats and crowded estates. The owners are all absentee landlords yet members of all the right clubs. Navigation through the replacement forests of think tanks and special interest groups requires a Privately Educated School System to groom the next wave of Alpha’s in the codes and signals required for flourishing.

The point is that all of this, all of it, was clearly signalled in 1979 with the election of Research Chemist, Margaret Thatcher in the UK and with the installing of the actor Ronald Reagan in the US and the resulting onslaught of neo-liberalist ideology that led to the systematic dismantling of effective democratic state structures and the mass sell-off of public goods at bargain-basement prices to chronically liberalised international financial markets.

Along with privatised utilities of life-essentials like water, coal, gas, transport and public housing came the neo-liberal wraith coming up the rear with the inevitable consequences arising of endless war, privatised military and the hijacking of the military industrial complex by gangs with political masks. The encouragement of massive corruption in the absence of state controls. The exploitation of Africa and Asia for her mineral wealth made inevitable by TIFF and TIPP trade liberalisation as with the continued ravaging of Earth’s resources for short term profit.

The World stares obliterative disaster in it’s ugly face, not only for the humans but for all the extraordinary critters and vegetable and arborial life forms. Shrouded now in our winding sheets, stitched together in sweat shops by children, using micro-plastics dredged from the oceans, we await the inevitable. Mostly with the percolated anxiety of cattle milling outside the slaughterhouse, sometimes with an oddly triumphant and wilful ignorance that seems to celebrate itself. Sometimes we wait frozen with despair or rage.

But mostly we carry on. Fighting, fucking, crapping, littering, music making, despoiling, loving, hating, boredoming, maniacal thoughting, opiated, close reading, not reading, mobile phoning texting, bullshitting, group thinking, micro exploiting, ageing, Being, transcending, being born. Hope, hopeless.

To be alive is to be Cassandra, the doom-caller. There are worse things, but I just can’t think what they are.

22.4.21

Epistemological Standpoints (Mark Fisher Project)

Georg Lukacs

History & Class Consciousness

III: The Standpoint of the Proletariat

5

Thus man has become the measure of all (societal) things. The conceptual and historical foundation for this has been laid by the methodological problems of economics: by dissolving the fetishistic objects into processes that take place among men and are objectified in concrete relations between them; by deriving the indissoluble fetishistic forms from the primary forms of human relations. At the conceptual level the structure of the world of men stands revealed as a system of dynamically changing relations in which the conflicts between man and nature, man and man (in the class struggle, etc.) are fought out. The structure and the hierarchy of the categories are the index of the degree of clarity to which man has attained concerning the foundations of his existence in these relations, i.e. the degree of consciousness of himself.

WTF!!! How dare you create a paragraph like this Georg! A spanking on the bare bottom is in order!!! I do not mean to be disrespectful but...really!

So the name of this mental foundation of thought processes is the wonderful STANDPOINT EPISTEMOLOGY. What a great descriptive! But what does it mean?

16.3.21

Essay4th! H P Lovecraft and the Art of Supernatural horror-Lovecraft's great Essay: Supernatural horror in Literature.

A mere 46 years old at the time of his death in 1937, Lovecraft is the father of what came to be known as Weird Fiction.

Lovecraft's extraordinary essay on supernatural literature and tales begins thus:

'The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.'

That's a lot of fear!

ENDNOTES FOR 2020

“In my whole life, I have known no wise people (over a broad subject matter area) who didn’t read all the time – none, zero.”

— Charlie Munger

21.11.20

DECEMBER NOTES

MONTAIGNE: Given the subject matter, “Of Experience” has about it a remarkably buoyant magnitude. Take, for instance, the following passage, as translated by Donald Frame in The Complete Essays of Montaigne:

It takes management to enjoy life. I enjoy it twice as much as others, for the measure of enjoyment depends on the greater or lesser attention that we lend it. Especially at this moment, when I perceive that mine is so brief in time, I try to increase it in weight; I try to arrest the speed of its flight by the speed with which I grasp it, and to compensate for the haste of its ebb by my vigor in using it. The shorter my possession of life, the deeper and fuller I must make it.

Propelled by verbs—perceive, arrest, grasp, make, try, try—the sentences wheel and wrestle across the page, resisting stasis at every turn, refusing to wait around. They achieve that mimetic, nearly miraculous work of performing the very action they describe. Here and elsewhere, Montaigne’s musings on mortality, his gripes about illness and aging, his love-hate relationship with the natural order, not to mention his fervent epistemological stocktaking, make for a stubborn blueprint for life in the red zone, an operative action plan for how to wring futility’s neck.

The ubiquity of suffering heightened Montaigne’s attentiveness to the complexity of human experience. Pleasure, he contends, flows not from free rein but structure. The brevity of existence, he goes on, gives it a certain heft. Exertion, truth be told, is the best form of compensation. Time is slippery, the more reason to grab hold.

In each of these apothegms, we find evidence of what Keats would later call, in a letter to his brothers, “negative capability,” a notion that F. Scott Fitzgerald, in his essay “The Crack-Up,” summarized as the capacity to embrace two contradictory ideas at the same time and go on functioning. “Of Experience” is one of Montaigne’s gravest works—“We must learn to endure,” he writes, “what we cannot avoid”—but the writing is so vigorous, so uninterested in despair. In the end, we get the sense from the writing that the writing was Montaigne’s method of magnifying enjoyment. Reading him might be as good a way as any to suspend life’s flight.

Drew Bratcher

---------------------------------------------------------

George Giacinto Giarchi graduated from the University of Glasgow in 1981 with a PhD in Sociology, and subsequently became Professor of Social Care studies at the University of Plymouth from 1977 to 2016. He is remembered in Scotland for his innovative social inscape study of the Argyll town of Dunoon in the 1970s - ‘Between McAlpine and Polaris.’

I am astonished to see how our lives intersected and terribly disappointed we never met. I lived in Dunoon in the early 60's and have some searing memories of that time that I will write about one day.

Also would love to read his study of the impact of the military industrial complex on a small Scottish town. But it's hard to get hold of.

3.10.20

‘Meaning and melancholia: Life in the age of bewilderment.’ Review of important book by Christopher Bollas by my bestie, Professor Jim Davis

‘Meaning and

melancholia: Life in the age of bewilderment.’ Routledge 2018

By Christopher Bollas. Reviewed by Jim Davis.

It was such a delight an inspiration for me to read this book. Here is a leading light in the psychotherapeutic world applying his creative and innovative psychodynamic thinking to a range of social, cultural and political issues.

My fear has been that the early-days ‘portrait’ of Transactional Analysis as a ‘social psychiatry’ has, mostly, come to resemble Oscar Wilde’s ‘Picture of Dorian Gray’, and that Pearl Drego’s call to transactional analysts to get out of our ‘psychic closets’ and involve ourselves in social movements for change remains largely unheard.

At the heart of this book, as the title suggests, is the fundamental importance of the search for meaning, and it is the process of searching that’s crucial as opposed to finding any definitive ‘truth’. As Bollas puts it, ‘Arguably, the quest itself (for meaning) constitutes the meaning to be found’. Indeed one could describe the book itself as an invitation to do just that. RSVP!

His view is that there has been a ‘longstanding turn towards cynicism and passivity in our culture, a loss of belief in ourselves which has grown across generations and is now a psychic fact of our lives.’ Socially this fatalism manifests as a ‘detached, cynical spectatorism, opposed to any active engagement and involvement…an abandonment of a commitment to social justice.’ With the loss of meaning, and the feeling that our lives can make a contribution, mourning has turned to melancholia, and we share the experience of a collective ‘bewilderment.’

Bollas begins his book, in the Preface, by referring to the disturbing victory of Donald Trump in America, the vote for Brexit in the UK, and the rise of right-wing populism in Europe. In doing so he offers us an invitation to widen our perspective from that of the individual, and even the family (itself shaped by politics, economics and culture) to the social, political and cultural realms. He enjoins us both a) to use our psychological theories to understand what is happening in our social world, and b) to account how ‘what is happening in our social world’ in turn shapes our selves.

Social, political, economic and technological factors create frames of mind which are shared collectively, and are transmitted from generation to generation. Throughout the book Bollas’s search for meaning can be seen as dialectical - a ‘dialogue’ that shuttles between two seemingly opposing perspectives – in this case the social (history, politics, culture, technology) and the individual - based on the underlying notion that it is the exploration of the relationship between the two perspectives that elicits meaning.

Bollas describes his book as a contribution to ‘political psychology’ and a ‘social psychotherapy’, and as an attempt to put psychological insight at the heart of a new kind of analysis of culture, society and history. He bemoans the way commentators tend to ‘shy away; from psychological introspection in explaining the ‘anguish of political phenomena’ and seeks to provide a ‘vocabulary and a set of perspectives that can set the stage for different types of conversations about our predicament’. For example he refers to the paradoxical phenomenon of white working poor Americans identifying with Fox News and pro-Trump billionaires, and suggests that this can be better understood psychologically - as an example of how oppressor and victim will form curious attachments to one another - than by means of socio-economic analysis. If we do not understand the ‘dynamics of this collective ‘charge’, we risk losing contemporary societies to ‘explosive entropy.’ This book is therefore also a call to action, both in and beyond our ‘psychic closets.’ As I have pointed out elsewhere (ref) ‘History tells us that slavery, racial discrimination, sexism, apartheid, colonialism weren’t seen as ‘social problems’ that anyone did enough about until the abolition, civil rights, #metoo, anti-apartheid independence social movements turned them into one.’

Bollas opens his analysis from the belief that in order to understand the present, and think about the future, we need to start with our history, and in the first few chapters he traces the history of the West (USA and Europe) over the last two hundred years. His aim in this is to make sense of how social, political and economic factors eg industrialisation, the horror of two world wars, colonialism, globalisation and technological change shaped the formation of collectively shared states of mind over many generations.

For example, in relation to colonialism, ‘By the 1880s the overwhelming power of Europe over the rest of the world sponsored a manic state of mind; fuelled by self-idealisation, they licensed themselves to ravage the world.’ He wonders, psychologically, how many Europeans allowed themselves to recognise the ‘murderousness’ of this colonialism. The optimism about ‘progress’ to be found in Western society throughout the 19th and 20th Centuries could be accomplished only by splitting, and projecting unwanted parts of self and society into the ‘other’….so when Europe colonized Africa it found its perfect ‘other’: ‘’savages’’ would contain the projective identifications of Europeans’ minds. They were seen to be primitive and violent so that the West could be sophisticated and pure.’ He describes this as a turning away from the reflective life, ‘burying ourselves in our ventures’, oblivious to the exploitation of the working–class and colonised people elsewhere in the world, which were seen simply as manifestations of the ‘natural order of things’’

As a former professor of English, Bollas begins his exploration of the impact of this social history on the fragmentation of inner life via reference to the literature of the early and mid 20th Century - Virginia Woolf, E.M. Forster, Camus, and Sartre. He portrays Camus’ ‘The stranger’ and Sartre’s ‘Nausea’ as ‘literary derivatives of two World Wars that crippled the soul of the Western self’. In place of the hero, we now have not so much an anti-hero as a negated human being; an absence of self and thought where once existed presence, insight and soul searching’.

I remember reading ‘Nausea’ (1938) and the impact it had on me in my impressionable youth. The main character, Roquentin, spent most of his time in the library (searching for meaning no doubt!). There he met a character whom Sartre named the Autodidact, whose knowledge of literature seemed truly extensive, that was until Roquentin realised that the only authors the Autodidact ever referred to had names, the first letter of which was between a and n, but never o or beyond. Turned out he was working his way through the entire library, from a to z in that order! Reading Bollas I realised that the Autodidact represented Sartre’s negated human being, a self without presence or soul searching, collaterally damaged from world war two. The ‘nausea’ of the title refers to the experience of life’s meaninglessness and absurdity, a characterisation that matches Bollas description of our most recent and current history as an ‘Age of Bewilderment’.

In a series of chapters which focus on how the social, culture shapes the individual, he makes that point that all individual psycho-diagnoses reflect the cultural mentalities of their time. He gives a number of examples, beginning with the emergence of the borderline personality in the middle of the 20th century, characterised by splitting, idealisation and projection. Bollas extends the idea of borderline as a ‘cultural suggestion’, a way of understanding how radical contradictions between ideological positions held within a society can successfully be kept apart, eg Remainers and Leavers about Brexit. It is precisely this borderline social structure that characterised post-war America, and enabled it to continue to idealise itself as the liberator of the free world whilst at the same time sustaining its war machine for the conflicts that followed. The split between the idealised America and the paranoid war-making America, between a country of promise and a country of profound racial prejudice, between its identity as a leader in the global community and an inwardly retreating nationalism, all served to create a profoundly confusing borderline ‘object structure.’

The cultural disinterest in inner life has also led to the formation of a new personality type – which Bollas calls the normopath. Unlike the borderline they are not filled with anger, but rather are those who seek refuge from mental life by immersing immersing oneself in material comfort and a life of recreation, fundamentally disinterested in subjective life. They are abnormally normal – seemingly stable, secure, comfortable and socially extrovert’ Normopathy relates closely to what Mark Fischer (ref) terms hedonic depression, characterised not only by the pursuit of pleasure but also a retreat into displacement activities such as addictive consumption, and a narcissistic withdrawal from ‘society’ and social issues.

In a fascinating chapter entitled ‘Transmissive Selves’ Bollas turns his attention to the shaping of selves by our increasingly technologically mediated world. Regarding the impact of social media he says ‘We may wonder if we have ever before walked so blindly into a mass transformation….with so little idea of where we are going.’ He argues that whereas modern media may seem in some ways to have brought the world closer together, in fact such immediacy has created a disguised form of distance - we are not closer, but further apart. Our lives and selves are based less on immediate experiences and more on those indirect perceptions ‘spawned by the information revolution’

Selfies for example do not reveal the self but rather an ‘other in a solitary act of estranged intimacy’, and when we abandon actuals to communicate with virtuals we are momentarily dissociated. Perhaps, even more fundamentally, Facebook, Instagram and Twitter and the like allow us to become, so to speak, part of the show. As we transmit our private selves to the world, we also become a function of that new technology - what Bollas calls the ‘transmissive self.’ We become both the vehicle of the communication, and ‘extensions of these objects as much as they are extensions of us’ Forebodingly, Bollas suggests that ‘A glance at the android future promises, not depth of communication, but a vision from the mental shadows. ’

In and altogether too short a chapter on the implications for what goes on in the therapy room, I was intrigued by the way Bollas developed Freud’s idea of the return of the repressed (ie the reappearance of unconscious mental content being expressed in a disguised form). Bollas coins the term ‘return of the oppressed’. ‘Wherever there is oppression of any form the oppressed self is forced to find compromised forms of thinking and expression, as a result of that oppression.’ By way of example, Bollas cites the idea of the ‘pseudo stupidity’ of slaves feigning various types of incapacity as a form of resistance, for example by ‘accidentally’ breaking machinery, or appearing unable to follow instructions, ie deliberately committing bungled actions as a defence and protest. ‘Part of the challenge facing the present-day psychologist is how to restore interest in being a subject in the face of oppression’. As a challenge relevant to all TA Fields, Bollas asks ‘What tools can the clinician use to analyse oppression and the ‘return of the oppressed’ in order to help the client find a space and a voice for reflective thought, expression and identity in relation to any form of oppression - racism, sexism, gender identity. (ref Ds CP, Johnson on gender, me on resilience)

Continuing in his shuttling back and forth in the dialectic between the individual and society, Bollas shifts his attention to the impact of Globalisation. Increasingly, and in a multitude of different ways, people have felt profoundly alienated by the world around them and seem to be in retreat from complexity and loss of meaning, seeking refuge in a search for a simplified view of life. This has fuelled the rise in fundamentalism, in protest about being governed by forces outside peoples’ understanding or control. It seems to me that Brexit has thrown up many examples of this pattern, eg ‘get Brexit done’, ‘take back control’ – political mantras that oversimplified complex issues, stirred up widespread fears, and appealed to swathes of voters in the recent general election. As Bollas points out, in the US context, this movement also represented a vote against the elite and remote government in Washington. He suggests that voters shifted from Obama to Trump (similarly, in UK: labour to tory) not because they were attending so much to the policy differences between the two, but because they wanted to ‘take back control’. ‘Emotions, not evidence based ‘facts’ (especially the ones that made people miserable) would be the new criteria for meaning making. If thinking something made you feel better it had to be right; if ideas made you feel worse, then they were bad and to be eliminated’

But, Bollas warns, the refusal to accept the complexity of life and the mind does not come without a price. It corresponds, he suggests, to what Freud meant by the ‘death drive’ - ‘the self’s retreat from a non-familiar world into the enclave of the secluded self.’ In the heat of the moment we can abandon complexity and opt for a simplistic version of reality, a more self- friendly version of things, and one based on paranoid projection onto others. Scapegoating simplifies a highly complex set of fears, and as Bollas emphasises, the group projection easily escapes reflective processes, pointing out that ‘the attack on Baghdad showed very clearly who really had the weapons of mass destruction’ Similarly, in Trumps projective identifications – Mexicans are rapists, fake news, ‘crooked Hilary’ -and his offering of simple solutions to complex matters, he is gauging the feelings of society and ‘organising them into a political rhetoric, which captures paranoid aspects of people’s imagination. Paranoid thinking works because it binds people around powerful feelings, and simplifies complex issues into digestible ones. ‘When political movements are based on paranoid ideas, the group process becomes all the more dangerous, as isolated selves discover there are millions of other people who share the same views. The retreat into paranoia then becomes even more deeply assuring and confirming’

In this way Bollas suggests that certain ideologies can function as ‘emotional and psychic holding environments’, such as in the appeal of the right wing neo-liberal push to reduce the regulatory functions of government. Regulation, they argue, is the enemy of freedom. Government is trying to take something away from us. These are felt, not simply as opinions, but as statements of fact, together with the belief that powerful forces in our world have taken away something that was cherished. This in turn evokes a sense of loss, abandonment and helplessness. ‘Fear, failure and impotence is a cocktail of emotions endemic to the marginalised’ and one of the ways out of this dilemma is to transform helplessness and depression into anger. In this way extremist views may represent a form of emotional, psychic holding in the face of extreme forms of dismay.

Deregulation, he emphasises, doesn’t apply only to the removal of the government’s regulatory functions, but extends more widely into a rejection of all forms of self and social regulation. Trump’s shameless expression of racist and sexist views is a manifestation of what happens when an individual abandons self-regulation. If this becomes widespread, it can result in a society governed by ‘id capitalism and primitive states of mind.’ Confronted by opposing views the paranoid feels under threat. Indeed anyone with opposing ideas is a ‘migrant seeking to cross the borders of the mind.’ This way of looking at things provides the paranoid self with a ‘powerful and pleasurable sense of cohesion in a world that otherwise seems contaminated by its opposite - plurality.’